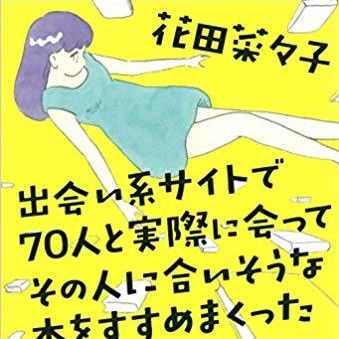

The Bookshop Woman by Nanako Hanada is a book that does what it says on the cover. Its original Japanese title, 出会い系サイトで70人と実際に会ってその人に合いそうな本をすすめまくった1年間のこと, translates roughly as A year in which I met 70 people on a dating site and recommended books that would suit them. The book is a memoir of a year in Nanako Hanada’s life (2013) which starts with her homeless, on the road to a divorce, and unhappy working in a Village Vanguard store which specializes in trendy nick-nacks and books, but fewer and fewer books every year.

To break out of a lifestyle that she is not enjoying, Nanako joins a “people-matching site she calls PerfectStrangers. The site has the tagline, “Spend just half an hour chatting to someone new.” Members post a profile and arrange to meet in a public space for a half-hour conversation. Nanako’s profile profile reads:

I’m the manager of a very unusual bookshop. I have access to a huge database of over ten thousand books, and I’ll recommend the one that’s perfect for you. (5)

Her memoir details many of the seventy “matches” with whom she meets and the books she recommends to them. It ends with a list of all the titles recommended in the book, as well as a list of recommendations for the reader of The Bookshop Woman.

For each meeting, Nanako describes the situation, her reactions to the person she meets, and the thinking behind her recommendations. Her skills develop over time as she begins to realize that not all her recommendations are successful. When one match responds to her recommended books “I read all of those ages ago” (56), she realizes that she needs to pay more attention to the person for whom she is recommending the book. She develops a rubric for recommendations, including ideas like “book might down better if you base it on general impression you get from the match, instead of going by facts” and “will they enjoy something totally different, or just slightly” (59).

This process of learning to recommend books to individual people is a healing process for Nanako. She seldom learns whether her recommendations were successful. She is not like Jean Perdu, the ‘literary apothecary’ of The Little Paris Bookshop who knows just the book a person needs in their life. If a recommendation is successful, it generally just means the match enjoys the book or at least decides to give it a try. When, near the end of the year, Nanako meets Yamashita, the owner of Gake Shobo, her favorite bookshop in Kyoto, she realizes that what she has been doing is what booksellers always do: meet strangers and recommend books to them. As Yamashita explains about the space he’d created:

Well, I didn’t choose the books for me. They’re not the ones that suit my tastes, they’re the ones that suit my customers. (152)

The process of meeting strangers, thinking about their interests or needs, and recommending a title to suit them is a cathartic one for Nanako. It requires her to pay attention to other people and provides a channel for connecting with them through the literature. She is now a bookseller in Tokyo, owner of Kani Books. The title of her sequel to The Bookshop Woman translates as I struggled with my two children of my younger boyfriend, a single father, and thought about the question of what a family is.

The publishing of her memoir has been as cathartic in its own way as was her year of making recommendations. Described by its London publisher as a “cult bestseller” in Japan, it has sold over 60,000 copies, translated into Italian, German and English, and been adapted into a Japanese television series starring Miori Takimoto as Nanako. The proceeds have allowed her to start her own store.